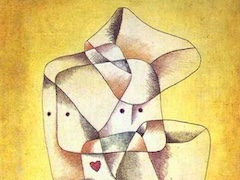

Revolving House, 1921 by Paul Klee

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Revolving House was painted during Klee's first months at the Bauhaus, where he taught from 1921 to 1931. During those years, influenced by the Constructivist environment at the school, Klee tended towards greater geometrisation in his work, though his temperament and creative spontaneity put him on his guard against any form of pure Constructivism. In the present painting he addresses the theme of the city, which he viewed as the place where nature is modified by man, and where law and order prevail. At first glance we see a deliberately naive image resembling a child's painting, in which the architectural forms have been reduced to their essential elements. Furthermore, Klee, in his persistent rejection of traditional perspective, shuns the single viewpoint and, as is frequently found in his work, uses a host of angles of vision which steep the image in numerous visual ambiguities. As we tend to regard architecture as something static, stable and constructive, we are surprised by Klee's introduction of a dynamic element into the geometrical conception of the houses, causing them to revolve around a centre, as if to imitate the rotation of a wheel. This dynamism makes his architectures living instead of static; unstable instead of stable; and intuitive instead of constructive.

Klee's untiring zeal for experimentation led him to employ unconventional artistic media. In this case, he has mounted on the paper support a piece of fine cheesecloth, s ecured fairly loosely in order to create an effect of three-dimensionality that is further heightened by the unevenness of the edges of the cloth. The colours are applied freely and unevenly in fine layers, without covering the entire surface. The weave of the fabric is thus visible in some parts of the painting and in others, where the paint is absorbed, he creates an intentional effect of texture which, coupled with the use of a range of earthy shades, imitates the properties of sand and cement. Driven by his desire to relate the theme depicted to the medium employed in order to explore the nature of appearances, the artist succeeds in reproducing in painting the materials from which these houses would be built in real life.

Klee's irrational ambiguity was applauded both by the Dadaists and by the Surrealists, but his magical world was by no means oneiric. At the same time, his relationship with geometric abstraction has made him one of the pioneers of abstract painting, even though his oeuvre is not at all abstract and was always in constant "dialogue with nature". It should not be forgotten that for Klee art was a "metaphor for creation" and he shunned the traditional artistic aspiration of imitating nature in favour of attempting to explain how nature operates. His essay Creative Credo, written in 1918 and published in 1920, began precisely with the famous statement:

art does not reproduce the visible: rather, it makes visible”